In this ongoing series, we ask SF/F authors to describe a specialty in their lives that has nothing (or very little) to do with writing. Join us as we discover what draws authors to their various hobbies, how they fit into their daily lives, and how and they inform the author’s literary identity!

I’m fond of saying that I was raised by brontosaurs—not in the “thunder lizard” sense. In my childhood, the adults around me were gentle, stable, contemplative, and slow-moving. Ours was a house of happy quietness, comfortably dim, paneled in dark wood, festooned with relics of the past. Mice scrabbled at night, hunted by capable farm cats. Faithful dogs waited in the yard, eager to accompany us on the next adventure. Inside, hooped quilts-in-progress cascaded past a dulcimer, an autoharp, a spinet piano. There were nooks and mysterious paintings, figurines, a working Victrola, a life-sized knight made of tin, and chimney lamps that Mom would light when the power went out, which was pretty often in rural central Illinois. The main rooms all connected in such a way that if you kept wandering, following a circle, you would end up back where you started. Visitors often expressed surprise over how the house seemed bigger on the inside. Once-exterior windows peered into other rooms, because Dad was always building additions, not unlike Sarah Winchester. My childhood was a world of 8mm home movies with scripts, papier-mache, latex monster masks, and prehistoric play sets. The imagination was indulged and creativity was encouraged, even when these required making a mess. Always, there were books, because stories were as essential as air; stories were among the very best of God’s gifts.

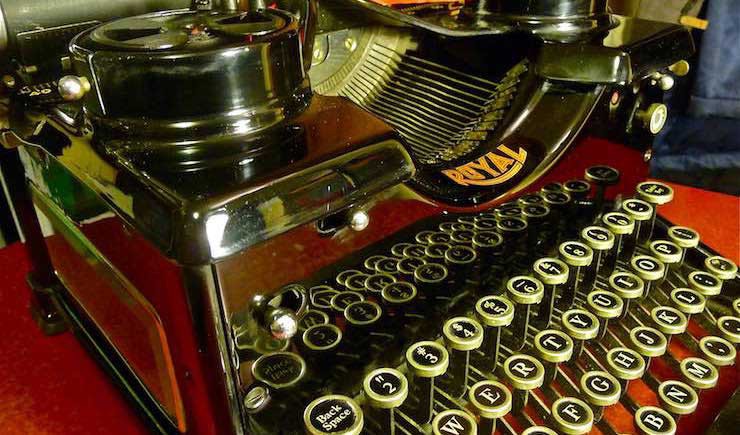

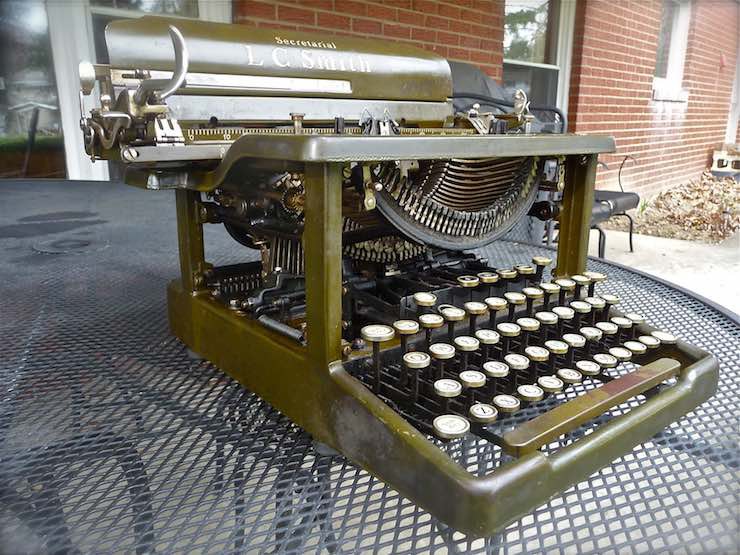

Back in the shadows, glinting atop a worn desk, was an L. C. Smith typewriter from the early thirties. My aunt had saved up for it and bought it when she finished high school. By the time of my childhood, no one used it but me. I was taught the proper reverence for it, and then I was free to clack out my little stories on it. Thus the twig was bent; thus the seed was planted in me that would grow, nearly five decades later, into full-flowering typewriter mania.

Why Typewriters, and Why Now?

We had to go away from typewriters in order to get back to them.

I learned to type on a big red IBM Selectric in high school, to the cadence of Mrs. Bowman’s Southern drawl calling out, “A-S-D-F. J-K-L-Sem. A-S-Space, J-K-Space, D-F-Space, L-Sem-Space …” The Selectric got me through college. It made my poetry for The Spectator and my papers for classes look good. But at about the time I graduated, the Power Word Processor was rolling out of the Smith-Corona factory, and I was enchanted. Never, I thought, had anything ever been so cool, so helpful to writers. The ability to correct and revise before committing to paper! The power to store text in a disc and print it all out again! The chance to change fonts! I left the Selectric and the Smith in the shadows. I strode into the future without looking back.

But now, in the early 21st century, something is happening, and not just to me.

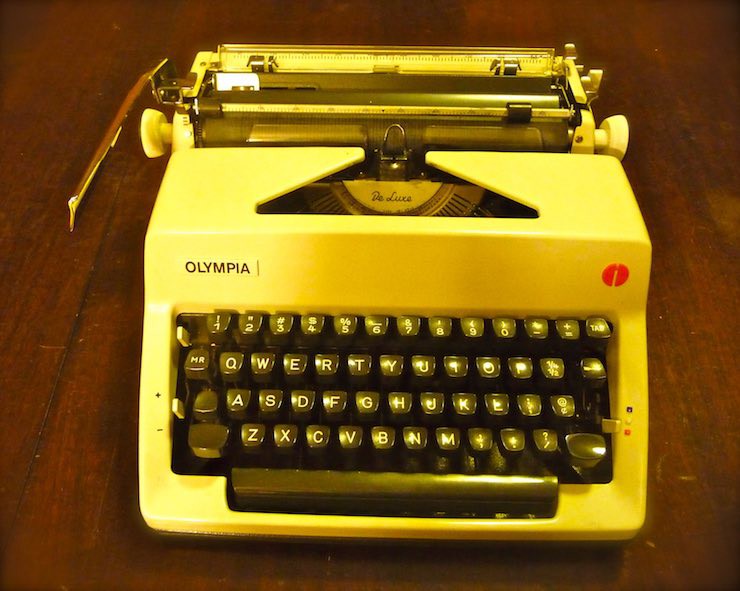

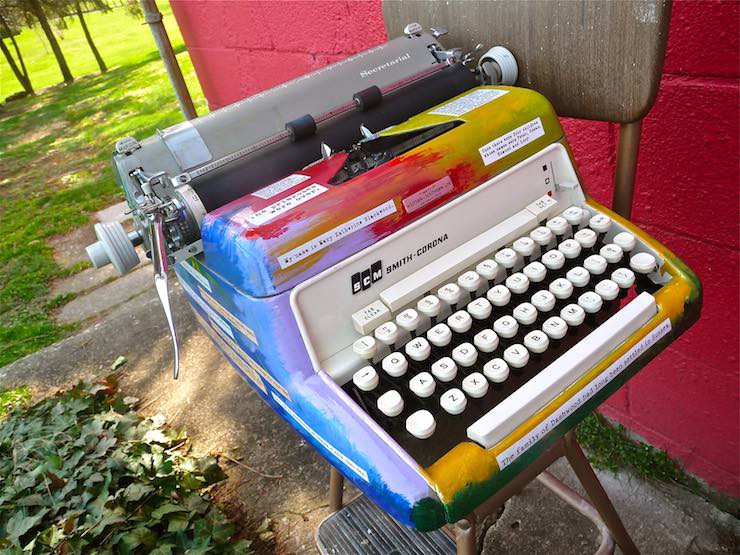

You’ve probably noticed the insurgency gaining momentum all around us. Ads use images of typewriters and fonts that look like vintage typeface. Typewriters are a hot commodity on eBay. The dust is swirling in secondhand stores as cast-iron beauties are being snatched from shelves. Hipsters are nearly as likely to be toting a portable Remington as a Mac, and people of all descriptions are tapping away from park benches. Preteens ask Santa Claus for typewriters. Law firms place a stately Royal on their bookshelves. Artists create pictures with typed letters and words; musicians record albums featuring typewriters as percussion. Street poets craft poems on request for passersby, banged out on typewriters. It’s happening all over.

I use the word “insurgency” not by accident. The notion is put forth by Richard Polt in The Typewriter Revolution: A Typist’s Companion for the 21st Century (2015). Polt’s thoroughly researched and truly engaging book is the Bible of the modern typewriter enthusiast. I won’t say it occupies a place on everyone’s shelf, because we haven’t shelved it yet. It’s on our desks and kitchen tables, usually open, or being carried around in backpacks and purses. We refer to it on the street when we’re gazing at the lovely old typewriter in the antique shop window; we review it on our workbench when we’re adjusting our typing machines. Polt succinctly covers the history of typewriters, the most popular models, how to clean and repair them, and what’s being done with them today, all in a lavishly-illustrated and highly entertaining book. The bookmark ribbon is even colored red-and-black, like a typewriter ribbon.

Polt describes the social phenomenon of typewriter popularity better than any other single source. Even for those not drawn to platens and glass-topped keys, his book is well worth reading as a study of contemporary culture. “The revolution,” declares Polt’s Typewriter Manifesto, “will be typewritten.”

I get some puzzled glances when people hear that I’m hunting for typewriters. “What do you do with them?” they ask. “You like them?” They want to know why—why a machine that can’t store text? Why a draft that must be retyped, not simply reprinted? Why choose slowness and smudges and irrevocable mistakes over smooth efficiency?

Oh, we still love our computers! I and all the typewriter enthusiasts I know like to save our writing and transmit it electronically and make use of all those fonts and search engines and formatting tools that the digital age provides. Am I writing this blog post on a typewriter? Nope—on a MacBook Pro (though many typospherians do write blogs now on typewriters and then upload the scanned pages).

You see, we’re not walking away from the computers—but, like the circular journey through that wonderful house I grew up in, life and experience have brought us around again to a fresh perspective. Following our own tracks, we’ve discovered an amazing space in which the new and the old exist side-by-side, each with something to offer. Most of us couldn’t see it as clearly when word-processors made their grand entrance, when digital writing appeared to offer unilateral progress and the sole gateway to the future.

We’ve lived with efficiency for long enough now that we’re increasingly aware of its drawbacks. We wonder who is watching us as we surf and browse. We realize the very options that can save us time are quite often wasting our time. As writers, we may shut the door and escape the distractions in the physical world only to plunge ourselves into another quagmire of distraction: social media, e-mail, articles, videos, shopping. We’ve set up our writing desks in the brunt of a hurricane, and we marvel that no work is getting done. Or rather, all the work is getting done, and all the play, and all the conversations are taking place as we whirl and cavort in the roar of the world. But we’re usually not doing that one thing we sat down to do. We’re not writing.

The typewriter is an utterly dedicated machine. It’s built for one purpose. To take up with it is to enter a tranquil state in which the instant-messaging window isn’t just closed for a minute—it’s not even an option. With the typewriter, we’re unplugged, off the grid, and we’re producing something that is itself an object of art, not just an intellectual property. Behold, here are letters impressed into paper! We have hammered, like Hephaestus at the forge. We have graven our runes, sounded our barbaric YAWP! Perhaps it is the first draft of a poem or story; maybe it’s a chapter of a novel. It may indeed be correspondence, part of a conversation with a friend—but it’s one conversation that has gotten our undivided attention. It’s focused and purposeful.

Typists will tell you that there’s something infectiously pleasant about the physicality of typing—the rhythm, the effort that it requires. I think it’s akin to taking a walk. That journey steadily forward, that use of the muscles—hand and forearm muscles, in this case—stimulates the brain in ways that the slouched, effortless glide of the flat keyboard does not.

Those who typewrite describe this difference in the process. With computers, we think on the screen; we try things, see how they look, and then fiddle with them. Typewriting is more of a commitment. We cannot stay and tweak; we cannot retreat. The words, when they leave our fingers, are going onto the paper for better or worse. If we don’t like everything about this foray, we can do it better next time, but not this time.

Typewriters train us to write in our heads, to think carefully before we blurt. Dare I say that such reflection is a skill well worth developing in this age of instantaneous communication? If more people weighed their words before the spew, wouldn’t the Internet be a more civilized place? I’ve heard many a professional writer say that the computer is too fast for good writing, that the slowness of composing with a pen, pencil, or typewriter allows the first step of editing to occur even as the words are still journeying toward the paper.

And this is what we’ve been seeking, what we modern writers have run so fast and far to attain: time alone in a world blissfully free of distraction, a world that demands steady action, that requires us to work.

One other benefit of typewriting early drafts is that it leaves a trail—a record that is both aesthetic and possibly worth preserving. As a digital writer, I leave nothing behind. When I make changes to my draft, I don’t save a copy of the old version. It’s no longer state-of-the-art, and I don’t want it around to confuse me. But if one works with a typewriter, the hard copy of every draft is there in all its marked-up, messy glory. The development of various story elements can be traced. In the years since his passing, much of J. R. R. Tolkien’s rough work has been published (Tolkien loved his Hammond typewriter, though he seems to have used it mostly for later, more finished drafts, preferring to write first in longhand). These formative drafts provide fascinating insights into Tolkien’s creative process and the gradual emergence of the Middle-earth we love today. They can also serve as encouragement to us, the fantasists who labor in Tolkien’s long shadow: many of his first-stage ideas were every bit as fumbling as some of ours, including Bingo Baggins (the first version of Frodo) who set out from the Shire not because of the ring or because Black Riders were chasing him but because Bilbo’s fortune had run out, and it was cheaper to live on the road than to maintain life at Bag End. Think of all we’d have missed if Tolkien had had a delete key!

The Hunt

There is a great thrill to it, the search for typewriters. It’s rare to find the enthusiast who owns just one. Each must answer for her- or himself just what makes and models are the must-haves, and just how many the budget and space will allow. Fortunately, preferences in writing machines are diverse, and in the present generation, it seems there are more than enough typewriters to go around, to keep us all happy. They are just elusive enough to make the hunt interesting and fun. They’re not everywhere, not at every antique store or yard sale. But we learn to keep our eyes open, and they turn up, rising from the clutter of the past like stones in a New England field. We become able to spot a Burroughs across a crowded room. We learn to spy a Hermes shining on a bottom shelf. Our hackles prickle and tell us when to turn and raise our eyes to a wide-carriage Royal, parked in the dimness like some ancient prototype aircraft.

Some secondhand shops group their typewriters together, giving us a rich banquet on a single tabletop. More delightful still are the shops that leave their typewriters scattered here and there so that we can hunt them like prized mushrooms, like Easter eggs. We race about, children on Christmas morning, wondering what awaits a room away.

Sometimes they find us. Once people know we’re typewriter nuts, our nets widen. Friends tell us what they’ve seen at a flea market. Relatives bring us old treasures in need of loving care. We enthusiasts locate each other; we buy, sell, and trade.

Of course we hunt on-line, too—eBay and Goodwill and Craigslist. But there’s nothing quite like finding typewriters in their natural habitat, out there among the barrels and dusty books and ladder-back chairs. That’s where they’ve been waiting for us, in the attics and closets, the spare rooms and basements and sheds, biding their time, waiting for us to catch up with them.

The Harmony

In the end, the writing life is about completing circles. It’s about finding the glorious spark that ignites on the page when the past and the present converge and arc. I’ve always said that we writers get our core material in the first five years of life. At least that’s how it works for me, in the craft of fantasy fiction. Those dreams and fears I had, those early questions and perceptions—that’s what I’m still writing about, though all my experience since then has added dimension and depth.

There are many circular parts to a typewriter: the cylindrical platen, rolling out page after page; the round keys, there to meet our fingertips and interpret our brains to the machine; the gears that make things move; the springs that spiral, pulling in the dark, tiny but crucial, working unsung—all these circles on the elegant inventions that have come around to meet us at the right moment.

For forty years and more, I was not ready for typewriters. I was absorbing, studying, living, learning my trade. Forty: the Biblical number of completeness … the years that Israel’s children wandered, till the generation was purged.

Now I’m writing with all the tools available, the old and the new. In my most recent book, A Green and Ancient Light, the main character tries to unlock the secrets of the past even as he learns to live in the present and begins to discover the future. It’s a book that I hope will whisper to the reader’s memory—for there are treasures there, in our memories, to be sorted from the clutter, polished up, degreased, and given some light oil. Their usefulness will be found.

Typewriters evoke memory. More often than not, those who see me typing will stop and come closer. They might close their eyes and bask in the clickety-clack, remembering Dad or Mom or high school. Or maybe they’re only remembering pictures, a technology they’ve vaguely heard their elders mention, and are wondering about this curious thing before them that is not quite a computer but has a lingering scent of age and metal. They will want to touch the keys and try the machine out. I let them.

But the typewriters themselves are manifestations of memory. They bear the scratches, the scars of long service. A few exude the hint of cigarette smoke, for offices were once filled with its clouds. Many of my “fleet” were out there churning words when the stock market crashed, when Al Capone was running Chicago, when Pearl Harbor was bombed. We humans go through many computers in our lives, but in their lives, typewriters go through many of us. In that way, they’re like violins, like ancestral swords. So I use mine with honor and treat them with respect. I try to leave them in better condition than I met them. I am not their first user, nor will I be their last. For now, in this brief moment when we work together, we will make the world different with our words. Hopefully, we will make it better.

Frederic S. Durbin is the author of the fantasy novels Dragonfly, The Star Shard, and A Green and Ancient Light, as well as numerous stories for adults and children. After teaching English for twenty years in Japan, he is a writing facilitator at a community college. He lives with his wife in western Pennsylvania.

Frederic S. Durbin is the author of the fantasy novels Dragonfly, The Star Shard, and A Green and Ancient Light, as well as numerous stories for adults and children. After teaching English for twenty years in Japan, he is a writing facilitator at a community college. He lives with his wife in western Pennsylvania.